May 26, 2019

In

Best Of, Roam

By

Nancy

Part two about our quick trip to Lebanon. The lure was to see a post-war, thriving country in the middle east with fabulous food and welcoming, cosmopolitan people. We found all of that, but I’m still thinking about some of the more nuanced and interesting things that surfaced. Next week, Itch returns to Italian subjects.

Arab or not?

After a civil war as divisive and destructive as Lebanon’s one expects to see the scars, which are inescapable, with many buildings still in ruins or riddled with pockmarks from gunfire. I wasn’t expecting to encounter, in an equally pervasive form, some of the beliefs about being Lebanese that fed the conflict.

Several of the Lebanese we ran into as tourists (our sampling was Christian) self-identified as Phoenicians, the Mediterranean civilization of maritime traders that flourished from 1500 BC to 300 BC. I got the first hint that there was a powerful, self-defining narrative from the advertising that ran on the Lebanese airline, Middle Eastern Airlines, while we flew to Beirut. Many of the ads were for banks, and all had a similar flavor: “You are a mover and shaker out in the world building businesses, trade, and making things happen. You need a bank to keep up with you no matter what port you are in or how much you are making.” Our tour guide at Byblos, one of the oldest continually inhabited places on earth and a thriving Phoenician port town, made the point, more than once, that the Lebanese are not Arabs, but Phoenicians, which explained their distinct look and more secular worldview. Which was NOT ARAB. This was an opinion echoed by several people we encountered during our short stay.

The Phoenician self-identification was used all through the 20th century as a shorthand for Lebanese nationalism, started by the Maronite Christians in the 1920s to differentiate themselves from the Arabs. I can see why it is attractive to be descended from the Phoenicians, creators of the alphabet, the zero in math, open-sea navigation, the color purple, and global trade, but I wondered if it was true.

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in England published research in 2017 showing that the modern Lebanese actually have inherited 93% of their genes from the Canaanites, who evolved into the Phoenicians, and lived in today’s Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Israel. The irony is that these genes appear equally among Lebanon’s population (as well as beyond the borders) crossing today’s religious, political, and cultural differences.

As Claude Doumet-Serhal, director of the archeological excavation which found the Canaanite remains from which the DNA study was based said, “When Lebanon started in 1929 the Christians said, ‘We are Phoenician.’ The Muslims didn’t accept that and they said, ‘No, we are Arab.'” But what was uncovered is that “We all belong to the same people,” she said. “We have always had a difficult past … but we have a shared heritage we have to preserve.”

Al Falamanki

I went to a monologue by Spalding Gray in which he talked about finding those “perfect moments” in life, which can never be planned or anticipated. The last night we were in Beirut we came across this restaurant, Al Falamanki which gave me my perfect moment for the trip.

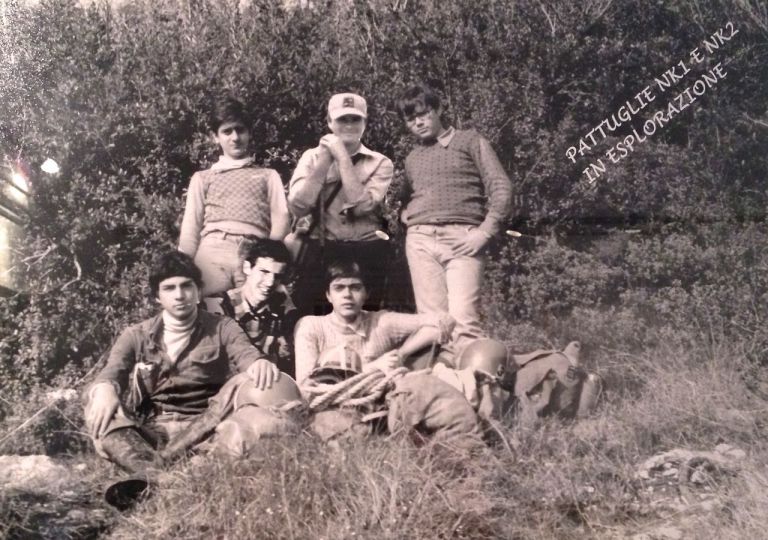

Opened in the 1960s the restaurant is open 24 hours a day and features live music, backgammon boards, and at least one hookah per person. There’s a large open courtyard at the center of it all and when we were there it was bustling and we were the only tourists. The guys from the photo at the top played a long game of backgammon, each with a hookah at hand, at the table behind us. Next to them were two couples on dates, and next to them a table of single women out for a night on the town.

We tried hard to find places to catch a glimpse of what modern Beirut is like, but this place did it for me. I’ve rarely seen such an at-ease and relaxed group of people having fun, and suddenly I understood what people love about Beirut.

Baalbek

In the infamous Bekaa Valley near the Syrian border lies Baalbek. I’ve seen a lot of Roman ruins around the Mediterranean and in France and England, but this site is extraordinary in scale and condition. It has been continually occupied for 8-9,000 years and has traces of buildings by the Phoenicians, Egyptians, Assyrians, and Greeks before the Romans built what is largely visible today. The temples often flowed from one god to another as the civilizations changed, often with the same focus. The temple to Jupiter is thought to be built on the earlier Greek temple to the sun god Helios. The other huge temple in the complex is dedicated to Bacchus.

If you ever have the chance, go.