Search and rescue—house hunting in Tuscany

When I saw where the “mad” brother had lived for decades, and died in the 1950s, his battered old clothes still hanging on hooks on the wall next to the bare mattress on the dirty stone floor, shaving cream still over the sink, I realized I wasn’t house hunting in the San Francisco Bay Area anymore.

As you might have guessed from the last Itch, when I shared how we purchased our house in Tuscany, nothing is predictable about real estate in Italy. When we were looking for a house to buy we’d already put down roots in our village—kids in school, good friends, about eight percent of daily life figured out, and we were falling more in love with our village every day. One of our local expat friends who had moved from our village to the next town over regretted making this change and said there’s no recreating the first love of your initial bonding with a town in Italy. This meant that we didn’t throw a wide net over several regions to look at “appropriate” properties but went deep locally, looking at every house that might be available in our immediate area, like the mad brother dwelling above. Before we were able to buy the house we wanted all along we looked at about fifty houses ranging from ruins to completely restored, each one a complete surprise.

When you look at real estate in America there is a certain set of assumptions that from my newly found perspective seem pretty boring and to lack imagination, like presuming there will be a kitchen. Here every viewing was an adventure—is there a foundation here under all the brush? Will the tree growing through the roof be difficult to remove? Is that a dead … rat? pigeon? Don’t step there or you will fall through the floor. Can you give me a leg up so I can break through this window to open the door? How hard would be it to put in a road to reach this place? And the nearly universal question, will this smell ever go away? The latter is usually linked to houses where there are still livestock living on the ground floor, but not exclusively. One house, which we were very tempted by, was particularly malodorous with pigs and geese under one part of the house, a dog kennel under another, and rounds of beautiful handmade cheese ripening all over the dining room table.

The American obsession with staging real estate has grown from the old trick of baking cookies during a showing to Oscar-worthy set design that seeks to erase any possible remnant of the current owners so that prospective buyers can imagine themselves in a neutral space full of possibility. If a cosmic antimatter to staging exists it would be Italian real estate viewings. Even at the nicest properties we looked at the agent arrived at the same time as we did, and as Italian houses have thick wooden shutters on the outside of every window and door, we entered with the agent into a world of perfect blackness. The trick during a tour of a cave when the guide turns out the flashlights to show complete darkness would work perfectly at the first stage of a Tuscan open house. The smell of damp, old belongings, and stone is usually pretty ripe. As you stand in the dark the agent goes from window to window slowly revealing where you are standing. Although a couple of houses we looked at were beautifully furnished and restored, where this reveal was a positive one, most had been left in some sort of suspended animation after someone had died, or a family had left. The close family had removed anything of value and left what remained, usually a rather sad hodge podge of old electronics, furniture no one wants, clothing, and the detritus of personal grooming products. Old tools abound. There is no thought to clearing out the buildings before they are put on the market. And often current owners are there for the viewing, watching every response.

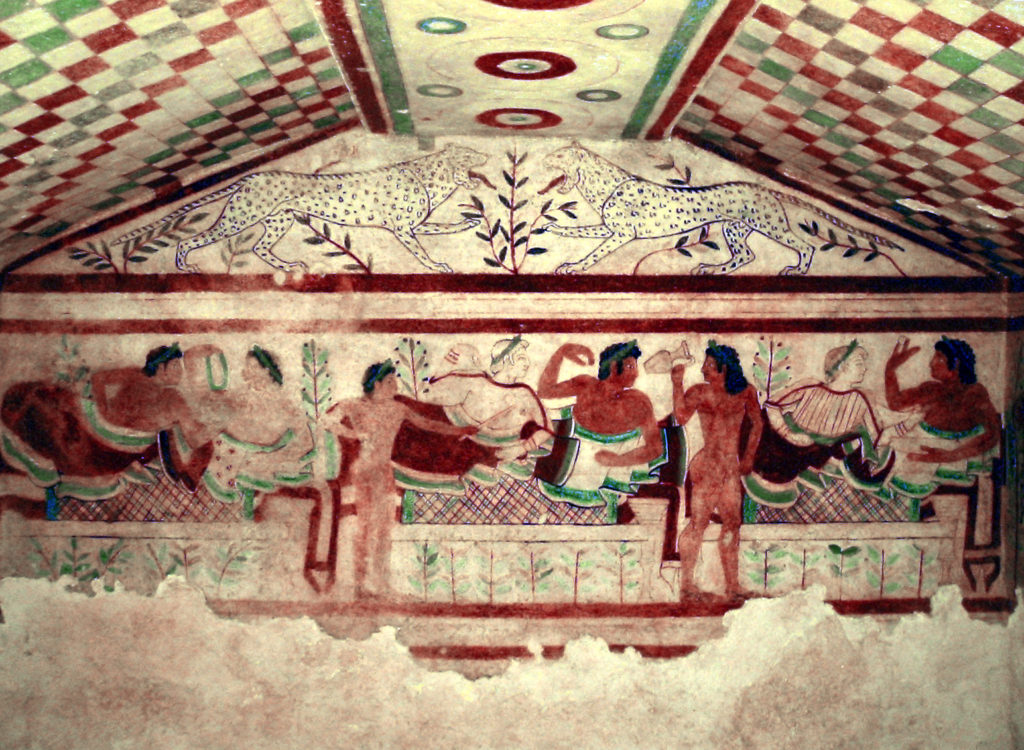

If you are lucky there are still glimpses into lost ways of life embodied in the walls. A hundred years ago Tuscan houses would often have stone sinks placed in the walls that drained directly outside—you can look at grass from the drain. Old stone fireplaces are common, although we saw a number of properties where thieves had gotten there first and hacked them out to sell. The ground floor of almost all dwellings were used to house animals—people lived upstairs—which helped to heat houses in winters. Many still have old feeding troughs and stone and brick corners of walls which have been rubbed smooth and semicircular throughout the centuries by animals scratching against them to give themselves massages. And yes, the smell of centuries of animals does come out after much sandblasting.

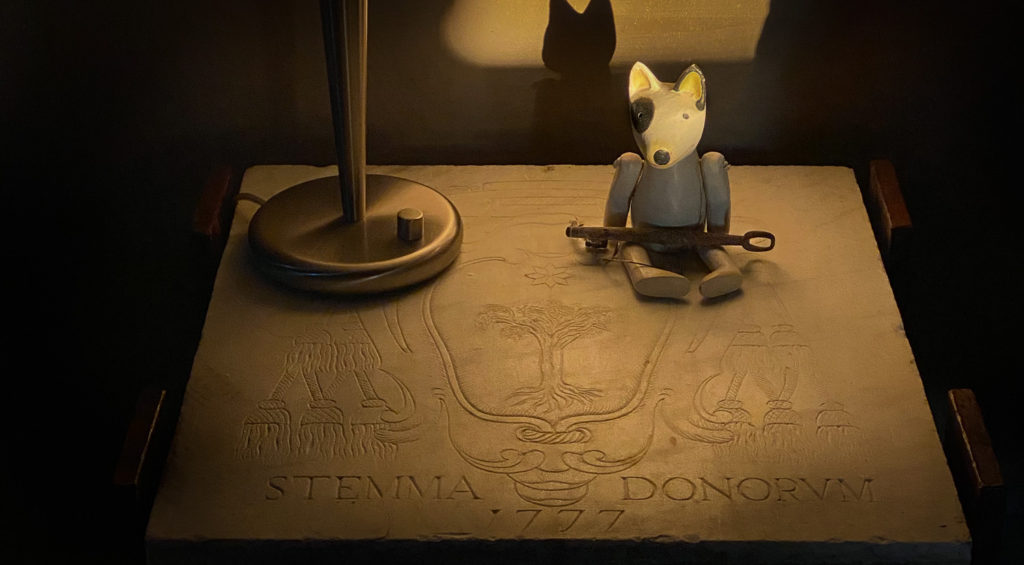

Some houses come with mysteries. We looked at one where Thomas Becket is said to have stayed when he came through town in the 1150s, commemorated by an ancient fresco. But even more mysterious, and easier to prove, is in the house next door to us that our friends just purchased—I will be writing about the restoration—that has three bedrooms, complete with beds with nasty mattresses, a small kitchen (so far all of this makes sense) and a bathroom with a tiny sink and toilet. There is not a shower or bathtub anywhere on the premises.

There’s an adventure and magic to the hunt here that I will always treasure, and even miss a tiny bit, leading me to drag visiting friends to view especially good deserted houses—with the side effect of increasing the Anghiari population by a couple of families who will be joining us when the properties are done. I love the unselfconsciousness and lack of preciousness of the process and, to me, it reveals more than just an abundance of deserted properties but also as a reflection of the Italian spirit. This is who I am, I am comfortable about the state I am in, and you can choose to be intrigued and go forward, or not. No presentation of perfection to tempt the slightly out of reach more perfect and evolved you that can exist if only you could acquire this house. Just don’t step on the goat poop on the way out.