How to buy a dream

Well, maybe not all dreams, but if buying and restoring a house in Tuscany is a desire of yours, here’s how it worked for us.

We knew from the start the house we wanted to buy, but it seemed impossible. The previous owner had lived there her entire life and died a decade earlier when she was in her 90s. She’d never married or had kids and it had passed on to thirteen heirs, some of whom we heard weren’t on speaking terms with others.

The house loomed just outside the walls of a beautiful village and on a quiet lane. It had been deserted for nine years, affectionately known by locals as the casa abbandonata, and the site of many a dare involving terrified kids trying to find a way inside. It was dark, shrouded by trees, and broken into occasionally, but we (and at least half the town) wanted it badly as it is in a terrific position looking up to the village and down to the valley, surrounded by a few acres, and a ten-minute walk from the piazza.

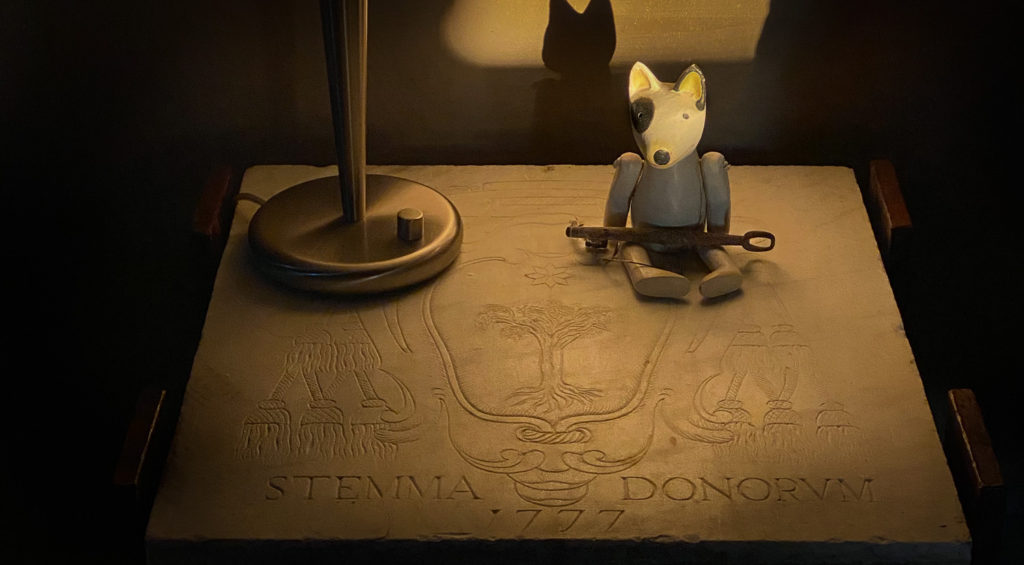

For years, whenever friends came to visit, we’d inevitably stand on the village walls which overlook the house and the land to “take in the view” but really to show them our dream house. We always added the caveat of “don’t point at it because if the village knows that the Americans are interested word will go out fast,” reflecting our American paranoia of potential bidding wars. Meanwhile the heirs, who seemingly agreed on little, were united that the best way to value the property was to add up what they all wanted to receive and use the total as the asking price, rather than getting a professional appraisal of what the place was worth and dividing by 13. The result was that you could buy a prime vineyard and restored villa in Montepulciano for what they wanted for the house. They hadn’t budged for nine years despite almost no viewings or offers. The house had been in their family since 1777, so a certain amount of irrational attachment was understandable. The villagers who had their eyes on the house had long given up and we had realtors tell us not to even bother trying to buy it because it was impossible.

In Italy the buying process can take years, if not decades (the family of one place we looked had thought about selling it since the 1940s but they still weren’t sure they were ready to part with it). Property taxes are very low, the houses are usually owned outright, and maintenance can be nothing as stone buildings take a long time to fall into ruin. It took us about three years to buy the house from when we first looked at it. We sent out some carrier pigeons about what we’d be willing to pay for the house and they sent out some return birds saying that would be acceptable. So we wrote up an offer with a two week response time excited to move ahead. Seven months later there was no answer and then fate intervened. Someone, or someones, to whom I will be eternally grateful, decided to break into the house and used a tree-trunk battering ram to break down one of the solid chestnut doors. (A villager later mentioned that she’d been driving by, recognized the intruders, and told them off. Can you imagine how embarrassing that would be from the villain’s perspective?) Suddenly, as there was a whopping 700€ of actual hard cost involved with the property to replace the door, the heirs were ready to do the deal. Yesterday. December was upon us and they were in a hurry to close before Christmas because they worried that one of their family, a woman in nearing 100, would die, passing her shares along to her two daughters who hadn’t apparently agreed on anything since 1940. Then the whole deal would have to be renegotiated. The heat was on and the closing date set for December 23, 2014.

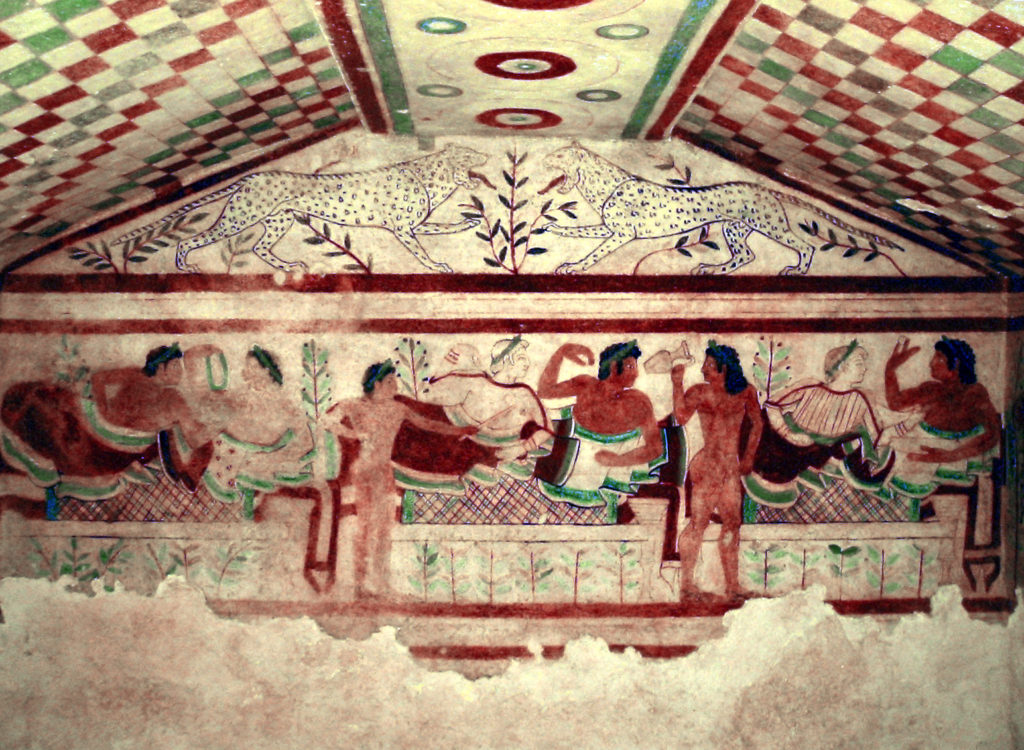

John and I had bought and sold a few properties in the U.S. between the two of us so we thought we had an idea of what to expect. As always, Italy is full of surprises. A notaio, or notary, reigns supreme over the sale. As Americans we had to get over our image of the guy at Kinkos with the book and stamp authorizing a signature. In Italy the role dates back to the Romans where they were the legal clerks for the Emperor. Their role evolved in the 1000s when a deed issued by a notary was given a privileged “public faith”, a particular strength. Today they must have a law degree to start, then specialized training to become one of a limited number of public officers of the State, guaranteeing that all parties to a signing are who they say they are and have legal authority to sell what they are selling. They also issue and hold the official deeds. Title company, registrar, and more, all rolled into one.

On the big day we all met at the notaio’s office. Very different from the U.S. where a closing often involves a trip into a sterile conference room at a title company to sign reams of paper, completely separate from the other party in the transaction, who you may never meet, an Italian closing is a spectacle. The office was large, lined with books, and had an enormous table in the middle. We were there along with the thirteen heirs, all seated in large blue velvet chairs. After everyone was assembled the notaio entered, formally dressed, with an air of gravitas. He took a chair, set apart of the others, at the center of the table. Then he started to read the document of sale. This long document contains the name, birthdate and place, fiscal codes, relationships, and percentages of the property of all the sellers. It details how much money each person gets, complete with the check numbers of the issuing bank. It then spells out in great detail exactly what parcels of land you are buying, with whom they are registered, and the relevant contents of the house, among other details.

As you can imagine, this document is long and tedious. Italian notaries have an ingenious solution. There is a particular rapid-fire reading style that they use, akin to an auctioneer, to get through the material. The blazing speed of this blitz of information did nothing to dull the interest of the sellers, however. They leaned forward listening to every detail of who got what, eyeing each recipients in turn. We finally got to the end and everyone signed every page wherever they want with the end document resembling a birthday card that a group has signed.

Then a special moment arrives when the notaio excuses himself. Traditionally this is when any applicable bags of cash are handed over to cover any gap between the recorded and actual sales price. We know people who have lugged significant numbers of paper bags full of money to finalize the deal, which fortunately we did not have to do. The notaio re-entered after a safe amount of time had passed, the keys were handed over, in our case a big wad of them including several antique keys, and big smiles, handshakes, and greetings were exchanged. The sellers, for all their initial reluctance, were warm and pleased that a new history with a family was to begin in their ancestral family house. The deal was done, and the adventure began.