The Most Beautiful Race in the World

Behind the scenes at the storied Mille Miglia race of historic cars.

Take a deep breath, forget your surroundings for a moment, and imagine yourself at the wheel of one of the rarest cars ever made, in one of the most famous races in the world. Don’t let the car that your mind pulls from the void be more recent than 1957. Preferably it is a convertible, so that you can better appreciate the sights and smells of the Italian countryside. You might want a hat, because the sun is hot, but you will need to secure it, as you will be going fast. And you might need to protect your hearing as your engine will be loud and deep, particularly as you downshift to ascend the long, curved, steeply uphill stretch right before you. A few minutes later you see another rare car racing at a fast clip on a flat stretch ahead, and you accelerate hard, managing to pass them. OK, enough imagination for you right now.

One year, we watched it outside a village with my car-obsessed nephew-in-law. We stood on the edge of the road watching these cars race by, then ascend a hill. My nephew-in-law could hardly speak fast enough: “Only one of those left in existence. That one has a special engine that they only made for one year. That one just sold for five million.” But more than the esoteric interest of how rare these cars are, what got me, viscerally, was the sound as they accelerated uphill. I’ve never heard anything like these deep, resonant growls that I could feel in my bones.

I’ve never been into cars—witness the Citroen Picasso I drove happily for five years—but the Mille Miglia stirs even my indifferent heart. These days it is more spectacle and less race, but it is still fantastically fun to have it come through our area, and this year it came right through the middle of our village. Here’s a random moment from us watching. They are slowing to stop at a checkpoint.

The route varies every year, and although it once came around the scenic perimeter of our village, this is the first time it has been routed down the steep, straight descent that is one of our defining features. How did that come to pass? I asked our geometra (a kind of mini-architect), whom I saw stamping the books of the participants to prove that they had reached this checkpoint. “Easy,” he said, “The head of the race is one of my best friends and when he was here having an aperitivo he saw our town’s straight descent, and knew it had to be part of the race.” This stretch of road is so steep that I witnessed many cars going back and forth to slow themselves, like I do on most ski slopes. When you think “failsafe brakes,” historic cars aren’t the first vehicles to come to mind. Listen to this one. Sound on!

he race was born in Brescia, a beautiful town not far from Milan (I wrote about it here), where some inhabitants like to claim they have gasoline in their veins instead of blood. In 1927, four men created an audacious race for the time, an all-out speed race over a course of roughly 1,000 miles of Italian roads, going from Brescia to Rome and back (mille miglia means a thousand miles in Italian). In 1927 there were 77 starters (51 finished), all of whom were Italian. Average speed was nearly 78 km/h (48 mph), and it took 21 hours and 5 minutes to complete.

The race quickly grew in popularity, attracting more participants from all over the world, testing their most technologically advanced cars. Except for a pause for WWII, the race continued until 1957, when it was stopped, deemed too dangerous to continue as a speed race. The race had gotten more than twice as fast— Stirling Moss set the record in 1955 with an average pace of 157.650 km/h (97.96 mph) in a Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR, and a time of 10 hours and 7 minutes, but still on the same tiny roads and through narrow village streets. Fifty-six people died in the Mille Miglia over its history—24 drivers/co-drivers and 32 spectators. An especially deadly year was 1957, when a Ferrari with a worn tire hit a cat’s eye reflector in the road and spun out of control into a crowd of onlookers, killing nine spectators as well as the driver and navigator. And that was only one of two fatal accidents. (This scene is a pivotal moment in the 2023 film Ferrari.)

In 1977, the Mille Miglia was reborn as a regulation rally. It’s famous for being the only time that many cars which are normally in museums are driven. Crews and large trucks full of gear follow the race to handle the likely breakdowns of these multi-million dollar wonders. The race attracts some car-obsessed celebrities with great collections—once I saw Jay Leno drive by.

But not all participants are millionaires, or famous. My friends, Jim and Joyce, caught the bug and acquired a 1953 Sunbeam Alpine, which now lives in the UK near a specialist mechanic. (This is the type of car that Cary Grant and Grace Kelly drove in the hills above Monaco in To Catch A Thief.) The Mille Miglia is hard to enter, but you can improve the odds. Only cars which were in the original races can participate. If a car had actually been in one of the original races it is easy to get in the modern rally, but it is also open to cars of the same makes and years of the participants. If you have a less common car for the Mille Miglia, like a Sunbeam Alpine, it’s easier to get a spot than if you have a car that more people have. Then you will be on a long waiting list. There’s even a helpful site that can tell you, if you are car shopping, which makes and models are more likely to get a place in the race. As my friend pointed out, at times around 600 cars had participated in the races from 1927 to 1957, so that’s a lot of cars to choose from—1503 eligible makes and models.

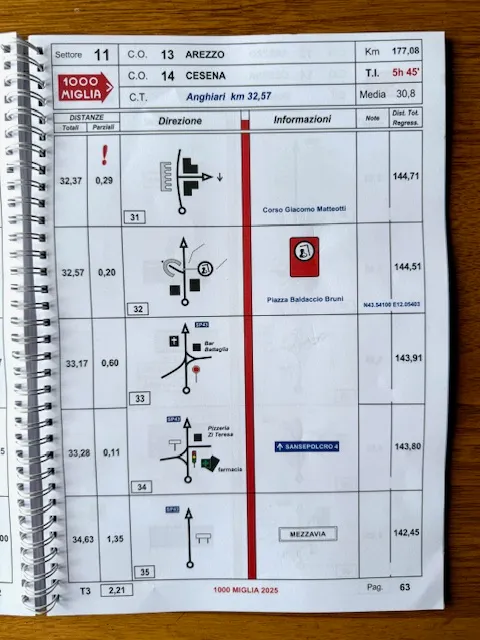

The objective of a regulation rally is to complete a series of segments of the course in exactly the amount of time specified—down to milliseconds. My friends described teams putting tape on their fenders and leaning out of the car to look under to make sure that the tape passes the mark exactly when it should. The team with the lowest score wins.

And it’s not all tame. According to Jim, on the open road the police will help to carve a path through traffic so that these cars can really let loose. Once we were on the way to lunch and found ourselves in the middle of the race. Full disclosure, we were, in fact, passed after we had a second to take this picture out of our back window.

The navigator is not just sitting there. Every race includes a book of route instructions, called “tulips”. At times, as Joyce and Jim discovered in the 2024 Rallye Monte-Carlo Historique that they participated in, the navigator can be yelling out split second directions as fast as they can “Hairpin turn L-R-L, tunnel, hairpin L”. When Stirling Moss did his record-setting pace in the Mille Miglia in 1955, he and his navigator did six reconnaissance runs and amassed 17 feet of race notes, which the navigator conveyed with rapid-fire hand motions. Here’s one page of the race book for our village.

According to Jim and Joyce, this race is a joy to participate in. The support and camaraderie of the participants and mechanics are unexpectedly enthusiastic and inclusive, even of the amateurs. My friends have been helped and befriended by one of the top drivers and support teams in the world, a couple of different times. But they said the best thing is to see the thousands of enthusiastic spectators lining the route, waving flags with the distinctive red arrow of the race, and cheering them on, delighted that these amazing vehicles are being driven.

And this year only five cars caught fire and had to stop the race.

Joyce and Jim have an amazing story about their first foray into European racing, when they entered their Sunbeam in the 2024 Rallye Monte-Carlo Historique, as complete novices. Jim drove the car from England to the assigned start in Reims, France, then they had to make it to the actual race start in Monaco. (The Rallye has cars start all over Europe and they have a set time to make it to Monaco for the start of the race, just to add a little extra challenge.) Their adventure involved car breakdowns, staying with farmers, helpful railway electricians rewiring spark plugs, and a race back to the UK for a crucial part. They even ended up meeting Prince Albert of Monaco—at his request—because his parents loved this car.