June 19, 2019

In

Best Of, Roam

By

Nancy

With time to kill at a horseshow in Umbria I decided to explore the nearby hilltown of Narni, which the Romans called Narnia.

First of all, let’s address the name thing. Yes, it is the inspiration for C.S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia, although it is unlikely he ever visited the Italian town. According to Lewis’s biographer and former personal secretary, Walter Hooper, Lewis read about Narnia in Roman history where it is mentioned by Tacitus, Livy, and Pliny the Elder. He had a Latin atlas in which he’d underlined the name “Narnia”. Lewis told Hooper that the name in the atlas had indeed inspired his fictional Narnia. This atlas was later given to the town.

To make things even more interesting, one of Narni’s local saints was named Lucy Brocadelli (1476-1544), who had religious visions starting at the age of five. She wanted to join the Dominicans but was married off as a young teen to a Count from Milan. She convinced her husband to let her live in celibacy. They lived together quite happily despite her propensity for giving away their belongs to the poor and wearing a hair shirt. The husband’s limits were reached, however, after she stayed out all night and came back the next morning with two men—who she claimed were John the Baptist and Saint Dominic. Her husband locked her up for Lent and when she went to church on Easter she ran away and joined the Dominicans. The Count was so angry he burned down a nearby Dominican property. She became a prioress, and received the stigmata (one of the few women to do so). Her benefactor, the Duke of Ferrara, started a new religious community for her but the Duke had the unfortunate habit of bringing his dinner guests by the convent after the meal and asking Lucy to make the stigmata bleed and go into ecstasy. After he died the others in the convent didn’t take well to this attention and locked her in a cell for forty years. After she died her body was discovered several years later to be “uncorrupted” and she was beatified in 1710. Her body is now in the cathedral of Narni. I cannot report on how corrupted, or not, it now is. She is thought to be the inspiration for Lewis’s character, Lucy Pevensie. (I swear on St. Lucy that this is actually the abbreviated version of the story. Please forgive my long digression—I’m still not sure it’s right to take you through this whole Lucy story, but I couldn’t resist.)

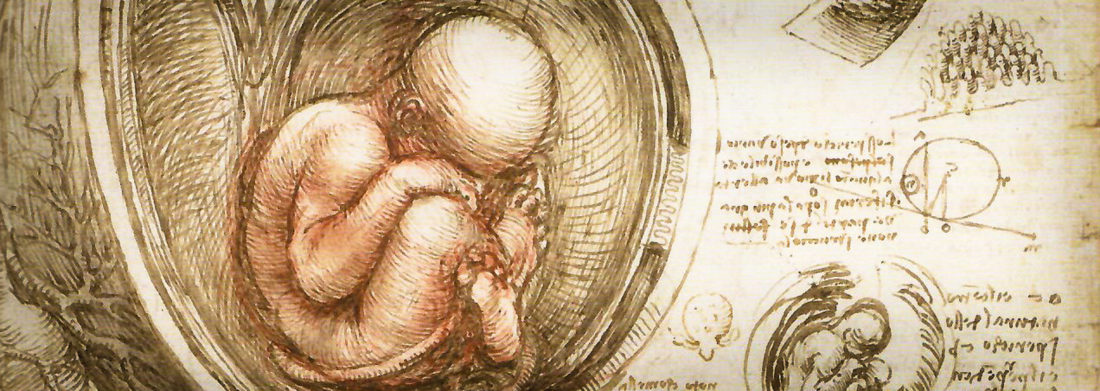

But there’s more Narnia in Narni—there’s an ancient, pre-Roman stone table that is outside of town. Local historians believe it was used for animal, and perhaps even human, sacrifice, which is not a surprise given the climatic scene in The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe.

Amazingly, there is hardly any reference to C.S. Lewis’s creations in Narni. (Unlike Dubrovnik and its dozen or more stores selling Game of Thrones junk.) It’s an enchanting little hilltop town perched between two valleys—a more gentle slope to the front of the town and a dramatic drop-off to the back. It has been inhabited since Paleolithic and Neolithic times and first named by the Osco-Umbrians as Nequinum in 600 BC.

It is my favorite kind of Italian town. Not too big and not too small. Gorgeous, almost unknown, very, very few tourists, friendly, enough of a critical mass of locals that it feels like it has a vital life of its own apart from visitors. You can visit a church from almost any century you choose, starting around the year 1000, all within the tiny center.

Here are a few of the different ones.

S. Maria Impensole from the 1200s.

S. Francesco from the 1200s with amazingly frescoed pillars.

For visual punctuation you’ve got the basic hulking fortress towering over the town and an abandoned Benedictine monastery perched on the backside of the town on a mid-ground range of hills.

I found out that it is close to the geographic center of Italy. I was almost fooled by the sign in the piazza in town, in several languages, saying that it marked the center of Italy, but dug a little deeper and realized that the actual point was a 10-minute drive up a dirt road to a parking lot and then a 30-minute hike through an enchanting woods, which would have done old C.S. proud. Didn’t see another person. Paralleling the hike there are openings into an underground channel, which turned out to be part of a Roman aqueduct system and still completely intact.

So here’s the for real geographical center of Italy.

Nearby happens to be a bridge from the 1st century, Ponte Cardona.

There was so much to do in tiny Narni that I returned for a second day to visit the underground Byzantine church, Roman cistern, and a Tribunal of the Inquisition, with adjacent prisoner cell, all discovered by chance in 1979. That’s for next week’s Itch.

Oh, I also went apartment hunting for you. Here you go.