An accident

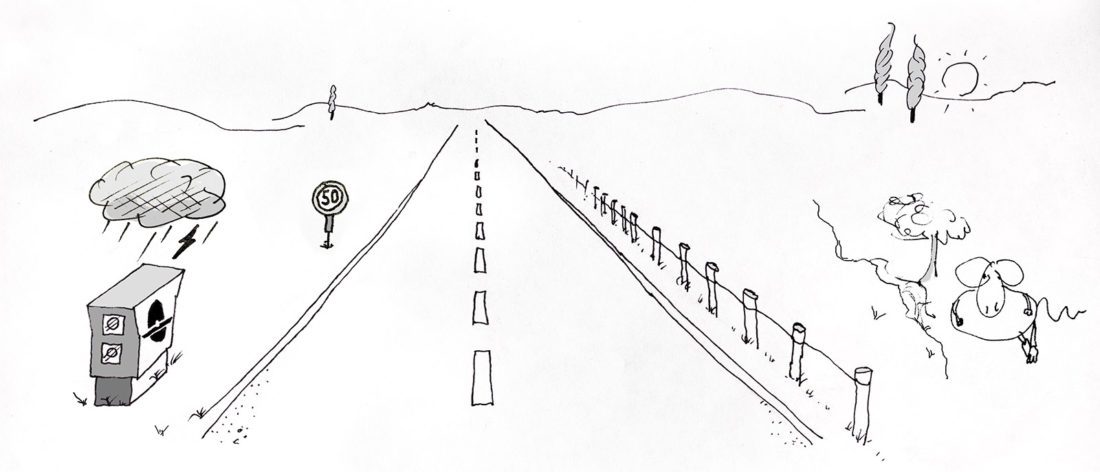

Friends of ours have a daughter who is a fairly new driver. She borrowed her parents’ car to drive a friend to the train station. A series of things made the drive to the station tense—they were running late, her friend had to make this particular train, and the car was almost out of gas. They arrived at the station with minutes to spare. The station had been newly renovated and she wasn’t sure where to go and pulled into the old passenger drop-off and said goodbye to her friend, tired and stressed. She got back into the car and as she tried to drive away there was a problem: a car was parked in the very small roundabout in front of the station with no driver in sight. A line of cars behind her was growing, as was her uncertainty about how to handle the situation.

She waited for a minute and no driver appeared, so she decided to edge past. She hit the inner side of the roundabout, hard enough to put dents in the car, bend the traffic sign, and lodge the car on the curb.

At this point the owner of the parked car reappears. He’s in his early 60s and with a younger woman. They head for their car to drive away. A person in the car behind gets out to shout that she needs to stop them and get their information. She calls her mother, who in the quick exchange assumes that her daughter had hit the other car, rather than the center post, also says that she should get the information of the driver in the other car. She approaches the two in the car she had needed to get around, who refuse to give her their information, as they had done nothing legally wrong.

She’s desperate. She’s wrecked her parents’ car, there’s a line of people shouting at her what to do, the people in the other car are refusing to give her the information she thinks she needs, so she physically stands in the way of the other driver’s door, blocking him from closing it.

Then things go really wrong. He grabs her to get her away from his door. She feels under attack and scratches his face. She calls her parents to tell them what has just happened. And that the police had been called and were arriving at the scene. Our friends say that they will be there as soon as possible.

When the parents arrived at the scene there were around ten police officers there and several police cars, lights flashing, and blocking the entrance to the station. They learned what had unfolded while they were driving and it was about as unexpected as possible.

They are met by a policeman who comes up with a big smile and says that he lives in their village and that his daughter had been in a local advertising video with their son several years ago when they were both kids. He had just had a long talk with their daughter that she needs to learn to approach life con calma. Their daughter is standing next to the woman, who turns out to the the daughter of the man who was scratched. Our friends’ daughter had been sobbing uncontrollably about what she had done and this woman had held her for five minutes while she cried. Their daughter had immediately recognized that she had gone too far in her anger and fear and kept going to the older man asking if there was anything she could do, each time crying harder as she saw the bleeding scratches. The man and his daughter were consoling her, saying that she could have been a member of their family, mistakes happen, and that we all react emotionally sometimes. The man’s daughter confesses that when she was the same age she actually hit an old man with her car, and that the scratches don’t really matter as her dad was already old and ugly. He agrees, and laughs. Our friend’s daughter learns that the man had double parked in order to come into the station and help his daughter with a heavy suitcase. Our friends tell us that this results in a fresh round of crying.

The officer who had had a long talk with her tells her that she needs to learn to expect that everyone is good and to always look for that. Another officer is preparing a police report and takes their daughter’s statement. Although she doesn’t say anything about the other factors that contributed to the situation the officer puts in the report that the girl was upset because she’d wrecked her parents’ car; the crowd, and her mother’s erroneous advice, had added to her reaction; and that she was a young driver and this was her first accident. The officer doesn’t mention the scratches, only that she defended herself with her hands. The officer remarked that she’s never seen such identical statements as of the girl and the older man. Three different officers apologized to the family and the girl that they need to issue a ticket for entering into the wrong place in the newly rerouted station layout, as well as for damaging the sign.

All begin to disperse and the man, and his daughter, come up to the parents and their daughter. There are warm wishes, forgiveness, humor, and graciousness.

Our friends’ daughter told her parents that this was one of the biggest lessons she’s ever had—that things like a double-parked car might not be a selfish thing but a father helping his daughter with a heavy bag; that is it possible to find the common humanity even after crossing into a dark abyss of rage; and that people can accept mistakes and move on; and, mostly, that people are almost always good. Also that sometimes you need to give yourself a time out before responding. Not bad lessons for a Friday night.