October 13, 2018

In

Live

By

Gianna Delle Valle

Itch is delighted to feature more from our Italian abroad, Gianna della Valle, with ideas about how to live more like an Italian no matter where you are. She has made a study of how to bring elements of the Italian way of life into her adopted, more frenetic homeland.

“Far bella figura,” or “make a beautiful figure,” is an Italian state of mind—and a national obsession. “Make a good impression” does not even come close to describing the rich combination of looks, gait, elegance, and manners included in the concept of the “bella figura.”

It means to dress elegantly and appropriately.

It means to have an elegant posture and gait.

It means to smash the objective you’ve set, whatever that is.

It means to stand out with your thinking.

It means making sure the light shines on you, no matter what.

It means taking centre stage and being the main character of the occasion.

It means to be the best at what you do.

It means people look at you and think “wow.”

It means to walk with your head tall.

It means to stand in tunica bianca (in a white tunic) despite adverse situations.

It means losing with class and without losing dignity.

It’s the full package, not divided into chunks with post-industrial taste: philosophy, fashion, interesting lives in social media, right ambition at work.

It’s the “sum being bigger than the parts,” a definition of “homo” with Renaissance smack.

It means to be able to navigate different circles successfully, of being able to be relevant amongst bakers and fishermen as well as millionaires and princes.

After something happens, parents question their children, bosses their employees, friends question friends: “hai fatto bella figura?” “Did you make a bella figura?”

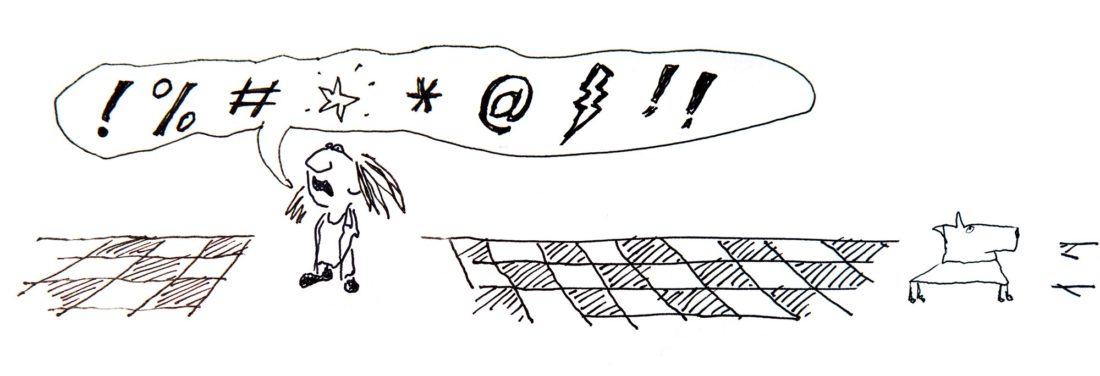

One often hears disheartened accounts of having made a “figura di merda” or “shit impression” with all the details of what went wrong, like a post football match replay after a loss. I remember in high school we even had a nasty jingle to highlight “figura di merda,” clearly a social deterrent for not having prepared well enough.

So dear fellows, companions on this journey on earth, and kind readers: stand tall, head high, put on your best face, and coolest trainers. Today make a wonderful, magnificent, victorious “bella figura.”