The village vs. coronavirus

What is life like under the shadow of the coronavirus in my small village in Tuscany? Much feels different since the weekend decree holding 14 million Italians in quarantine in the North, and just finding out we are included in the lockdown. Some things remain the same, like my daily walk where I often see locals out for trail rides.

The villages of our valley issued a statement that in addition to all schools being suspended (preschool to universities), so are sporting events, public and private events, including theaters and cinemas, all civil and religious ceremonies, including funerals (?!), discos and clubs. Visitors to hospitals and nursing homes are strictly limited. Businesses, cafes, and restaurants remain open but must guarantee that any patrons are at least one meter apart. If the measures are disregarded the punishment is three months in jail. Everyone who just fled Milan is supposed to self-quarantine for 14 days.

A friend in Milan was sharing her large consulting firm’s response to the virus (this was from last week, not sure how it has changed as of today). All entrances were closed except for one. Everyone entering and exiting had their temperatures taken. No more than two people in an elevator.

Our local grocery stores are still well stocked, including toilet paper (still don’t quite understand the run on that in the States) and we are working on our hand sanitization routines. Ok, load bags in car, return cart, sanitize hands and bottle before unlocking car. Drive home. Unload bags. Shit! Now the contaminated bags are in the kitchen!!

I saw an elderly man at the shared sink outside the bathroom at a tiny local restaurant counting while thoroughly washing his hands. Another man was doing our disinfection dance outside his car after exiting the pharmacy.

The pharmacy is one of the great things about Italian life. It’s the first line of defense for all matters of health with smart, trained pharmacist/doctors who consult with you about minor health issues, do small procedures, and give prescription medicine if they deem appropriate. Now only one person in at a time can enter and the counter cordoned off so all customers stand over a meter away from the pharmacist and register. The best thing is that they have contracted with a local lab to make hand sanitizer. Pretty impressive with only two stores.

There is suddenly a big push on social media to not go out in public, complete with its own hashtag #iorestoacasa “I stay at home”.

Where am I in all of this? Trying to adhere to #iorestoacasa despite my hatred of being cooped up. We live in such a small town that work, travel, hanging in cafes, and having lunch out every day are my escape valves, and now I don’t have them. I had to do an errand this morning and passed a cafe with tables in the sun where I badly wanted to stop and have a coffee but decided not to. I feel so cognisant of how many elderly people there are in our village and I want to protect them as much as possible. Unfortunately Donella and Sebastian cannot return from London for Easter. It’s fascinating to me that London and Donella’s university, UCL, one of the most international universities in the world, are taking so few precautions. According to Donella, London is 100% normal with the exception of a shortage of hand sanitizer. She is required to attend 200 person lectures and they have given no guidance to avoid the London Underground, nightclubs, or pubs which are in full swing. Quite the contrast.

I am tremendously proud of my adopted nation for how transparent and economically selfless the government has been so far — particularly in comparison to my birth nation and the UK which seem to be driven by politics rather than public safety. Testing is abundant, health care free, and people, at least here, seem to be aware that this is important and want to cooperate.

And there’s comfort in the age of this place. That the core of my house used to be a defensive tower in the middle ages, which I am sure has seen its share of people sheltering inside with the huge wooden doors closed. Embracing waiting and uncertainty is hard for us, and I am sure it always has been, and it feels like something I need to look in the face right now.

Meanwhile I am loving the Italian sense of humor which is coming out in full force on social media. A 30-something relative of John’s who grew up the same tiny village in Calabria where John’s grandparents lived (but now lives in the north) posted this:

It means “Nothing works, factories closed, nobody at school, cash is hoarded, refrigerators are full. All of Italy seems to be Calabria.”

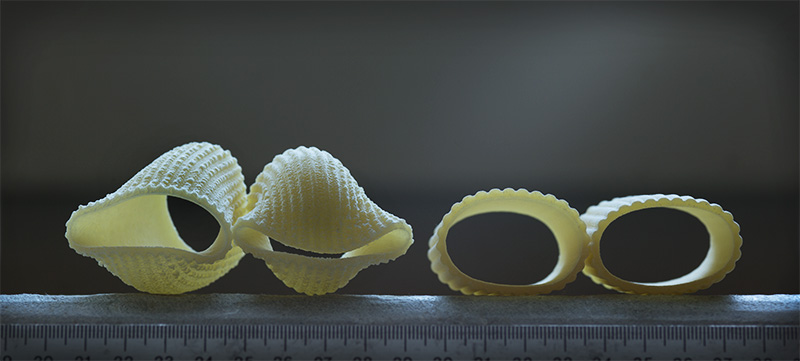

Apparently the North/South divide of, well, everything even extends to pasta. Quartz had an article that in Milan the pasta aisle is often bare with the exception of the fully untouched penne lisce boxes. Penne comes in two varieties, striped or ridged, rigate, and smooth, liscio. The Northern Italians scorn the smooth type, apparently not even deeming it adequate to eat during a quarantine, while Southerners, particularly around Naples, prefer it. (That preference transferred to American Italians with the emigration from the South.) Northerners claim that the ridges hold the sauce better. Southerners believe that the ridges cook before the inner part of the pasta resulting in the outer layer becoming overcooked. And that the ridges were a by-product of the industrialization of pasta and the shortcuts that lowered the quality. A Michelin-starred chef from Naples, Gennaro Esposito, was quoted in the delightful Quartz article as saying that penne rigate was “the apex of weak thought.”

A couple of baristas from a local cafe who are as close to Brooklyn hipsters as we get put a series of memes about the village on Instagram. I loved one of their latest. It’s a comparison of the village with, and without, the virus. We are so remote it’s like we are quarantined most of the time.

Today I decided to get cozy and make comfort food for lunch as we decided not to go out. Here’s what we made:

Pasta alla siege

Free form recipe but amazing. We sauteed three yellow onions and then added pork sausage to brown well. I had made some of Skye Gyngell’s Slow Roasted Tomatoes that we added (about a cup of them), a two of jars of chopped tomatoes, bay leaves, loads of black pepper and dried red spicy pepper, red wine, a few dried porcini, and a pinch of organo. It was hot, a little sweet from the roasted tomatoes that added a nice complexity, the porcini gave it a rich undertone. Pretty darn good for a siege.