In an Italian Hospital

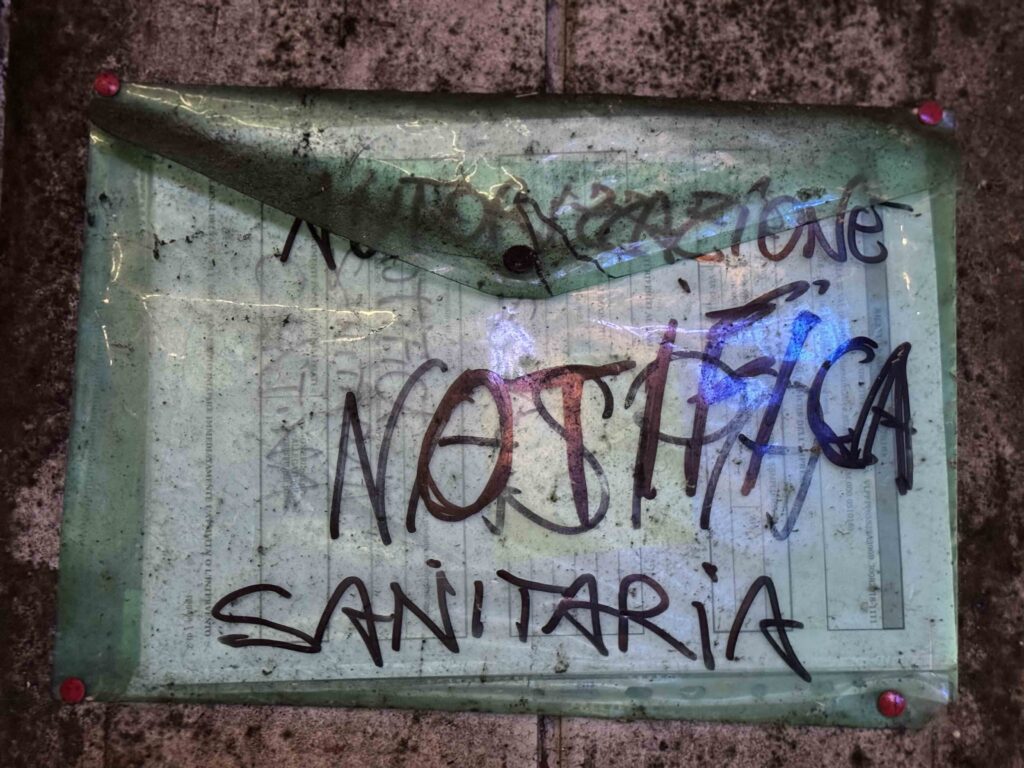

(Don’t worry, everything is fine. Explanation of the photo above is for those intrepid readers who make it to the end.)

Like so many aspects of our life in Italy, the medical system has been full of surprises.

The first few times I went to the local hospitals I was pretty stunned. Many of the facilities were built in the 1960s, with that certain ambiance that only hulking cement structures with interiors that have that special-shade-of-green walls, plastic chairs, and fluorescent lights can deliver. I’ve sometimes spent half of an hour finding where I am supposed to go in these large labyrinths. If you are admitted for a stay, the food is notoriously terrible, so family members often bring in home-cooked dishes.

A few years ago, one of my doctors determined that I needed to have a procedure, which required a trip to the hospital. On the day of surgery, we wandered around until we found the correct waiting room, which was next door to the well-marked morgue.

Soon, I was lying on the gurney, waiting for surgery. No one asked for my name, date of birth, or to confirm the procedure I was about to have. Instead, my doctor/surgeon greeted me by name and was telling me stories about his teenage son who wanted to become a videogame developer and asked if I have any leads in California. The nurses were touching me, a lot. They patted my head and used my body as a desk, resting their clipboards on my stomach to take notes. As they were petting me I was told that all would be fine.

I was wheeled into the operating room and moved onto the table. I said hello to the crew, but I didn’t meet an anesthesiologist. I joked that I was a little concerned by this, and they told me that she was finishing her coffee and would arrive shortly.

A man came in wheeling an instrument they needed, replacing one that wasn’t working. My doctor/surgeon said to the technician that he’d never used this piece of equipment before, and was told that they all worked pretty much the same. Before I had time to worry, I was out. Guess my anesthesiologist had finished her coffee.

Next think I knew, I was in post-op, struggling to regain consciousness while petting my dog, Lola. In the hospital bed. Cuddled next to me. In the recovery room. John said that he went outside to give Lola some water, as she was in the shade under a porch on a really hot day. The nurse said to bring her in—Lola would be cooler and it would do me good to recover with her next to me. And it did.

And I never saw a bill.

Italian healthcare is often ranked #2 in the world, after France, with Italians having one of the longest lifespans in the world (all delivered at one of the lowest cost per patient globally). The quality of care varies from region to region, and we are lucky to be in Tuscany, which is one of the best.

I got a call at night from a friend whose husband had become oddly lethargic and unresponsive to conversation. She needed help getting him to the hospital as they live up a rough dirt road, and the ambulance (which is free, BTW) couldn’t get to their house. We called on a friend with a four-wheel drive to get him down the driveway to our car, and we drove him to the emergency room.

The doctor was puzzled by what was going on. Our friend was very fatigued and running a slight fever. The doctor wanted to be cautious, so she kept him overnight for observation. And she kept him for two weeks while she figured out what was wrong. Turns out he had sepsis resulting from a previous infection that hadn’t fully resolved. A more pressured hospital environment, motivated to get people out quickly, might have missed this condition as it took a persistent and curious doctor, observation time, and many tests to diagnose. And sepsis is a very serious, sometimes fatal condition, especially in older adults.

And they will never see a bill.

Sebastian was about twelve when we went to his new pediatrician for a check-up. Mid-exam the doctor said that she wanted to introduce Sebastian to her daughter, who was about his age. She got out her phone and called her daughter to have her meet Sebastian. (We happened to catch the moment above.) She followed up with us after the visit, and arranged to take them both on a “date” for the afternoon to a local pool. After that, his doctor and her family invited him on vacation to Calabria, which he declined. Almost a decade later, Sebastian remembers this with great amusement and affection, and reminded me of it for this article.

All check-ups are free.

The photo at the top was taken by John years ago when Donella was in a horse show. Things unfolded in a split second, and what he assumed he was getting—Donella and her mount sailing over a jump—turned out to be an unexpected parting of ways between human and horse. She landed on her arm, hard, and was in a lot of pain afterwards. We went to the emergency room to make sure there wasn’t a fracture.

We were sent to orthopedics, and her exam and X-rays took longer than they should have because all the doctors were laughing so hard at the photo. They would ask her a question, start to diagnose, and then see someone walking by the door and have to call them in to see the photo. I think she made the day of dozens of doctors and nurses that day, and it turned out to be a bad sprain, but fortunately not a break.

And we never saw a bill.

I haven’t yet figured out when payment is required. For blood tests and scans that are follow-ups to regular doctor visits there is a co-pay, on a sliding income scale. It is usually less than €50. But emergencies and more serious treatments seems to be completely covered. I see certain doctors privately for exams, but if there are any treatments needed it gets put through the public system.

It’s not always warm and fuzzy. I get my mammograms by being sent a letter telling me to show up to a mobile mammogram truck at a certain time. I arrive and knock on the door of the RV. A male technician opens it, gestures towards the machine, tells me to take off my shirt and proceeds to prod and squish. All in plain view of the unlocked door. This is not the experience I was used to in California with background sounds of whale calls, soft lights, and cotton gowns.

But, I never see a bill.

What I love about these experiences is that the personal and the professional co-mingle. I am sure that this is partially because of a different litigation climate, but I think there is more to it. As we found in schools, there seem to be fewer people hiding behind their professional masks, bolstering an aura of authority. Most people here are completely normal in their professional roles—more like what you’d expect if you had a coffee with them—while delivering excellent results. There’s something so self-accepting and confident, so relaxed and competent about many of my interactions with Italians that I love to see this attitude extend into the high-stakes world of medicine.