August 2, 2018

In

Live

By

Nancy

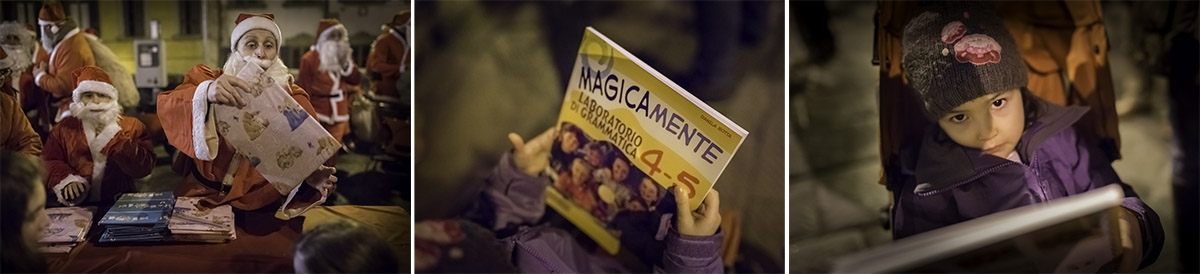

Growing up in the United States, I somehow missed out on learning that there is an Italian sport that involves rolling cheeses. My first clue that my sporting education might not be complete is a photo on the wall of one my favorite workers’ lunch restaurants. In it, the chef is holding a large wheel of cheese. He’s poised to throw it, much as if he were about to roll a bowling ball.

My next brush with cheese rolling happened as I was driving down a Tuscan backroad on the way to the grocery store. I noticed a group of men—including the chef— standing together, looking very serious, all well-armed with large cheeses. I’d like to say that I instantly pulled over to find out more, but wasn’t brave enough—they were having such a good time among friends that it like intruding, and I’m not yet confident enough about my Italian.

The third time I spotted a cheese in play, it was a solitary man, practicing his cheese roll, and I wasn’t going to let this opportunity pass. I was with my fluent daughter, and she owed me one because I had just picked her up at the horse stable, so “we” found out when the next competition was happening and asked if we could come and film.

As is appropriate with cheese rolling, my search came full-circle when I interviewed the chef—whose picture hangs in the restaurant—about the basics of the sport. I was surprised that he has only been participating in this sport for three years—so for those of you who think “It is too late for me to learn to roll a cheese” there is hope yet.

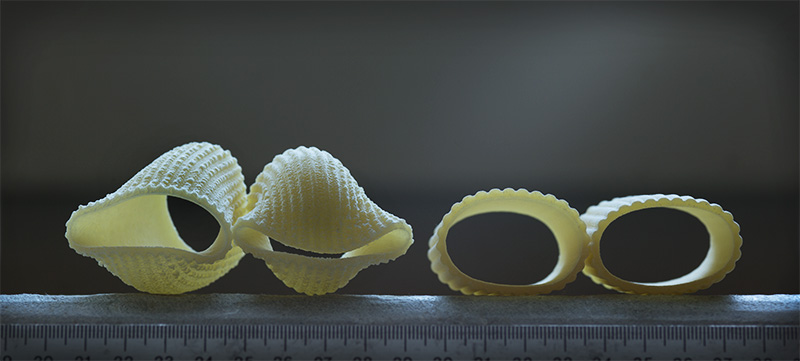

Each team of two has a large, flat, hard cheese between them (could be pecorino, asiago, or parmigiano; but all the teams have to use the same kind.) They attach a leather strap around the cheese, which creates a sort of handle, that enables them to launch the cheese, rolling it down the road. The team who cheese goes the farthest with a predetermined number of throws wins.

Cheese rolling is an all-day sport. The day we came out to watch, they had been out rolling cheeses since 8 in the morning and would be doing so until about 7:30 in the evening, covering around 9 kilometers on foot.

Cheese rolling dates from Etruscan times (the local tribes living here pre-Roman times, whom Tuscany was named after). It’s even included in the Federation of Italian Traditional Games and Sports (figest.it), an organization that holds competitions and publishes the rules for about 15 ancient games like, tug of war, cross bow shooting, darts, and very obscure games like morra, which dates to the ancient Egyptians. (For a lovely little blast of morra: https://www.facebook.com/MorraMarche/videos/978697128831911/)

In cheese rolling there are five different weight classes—cheeses ranging from 1.5 kilograms (a little over three pounds) to 25 kilograms (55 pounds). Hurling a 55 pound cheese down the road takes serious training and muscle!

My favorite part is that the rules specify what to do if your cheese breaks during competition. First feed the spectators cheese, then you can replace the cheese and carry on.

Our chef friend says they always serve the cheese after it has had its moment of competition and that it is particularly delicious. The rules dictate that, after the competition, the winner provides everyone else with glasses of wine. But victory is sweet after all, because the victor gets to keep the cheese of the defeated.

The crates of olives are unloaded and weighed with great import, carefully watched by the others in line for the press. It’s a competitive “I have more olives than you” moment. We do respectably well, olives weighing in at over 500 kilos (over half a ton), in 25 crates. But soon we are put in our place by three very scruffy 40-something guys who came in after us, unloading about 75 crates. “Smug devils,” I think to myself. We eye them. They eye us. No smiles.

The crates of olives are unloaded and weighed with great import, carefully watched by the others in line for the press. It’s a competitive “I have more olives than you” moment. We do respectably well, olives weighing in at over 500 kilos (over half a ton), in 25 crates. But soon we are put in our place by three very scruffy 40-something guys who came in after us, unloading about 75 crates. “Smug devils,” I think to myself. We eye them. They eye us. No smiles.

The town wildly embraces this annual tradition. There are 130 seats for each of the 10 shows and tickets sell out almost immediately. I went to buy mine the morning the tickets were available, arrived 15 minutes after the office opened, and found myself 66th in line. The entire process took hours!

The town wildly embraces this annual tradition. There are 130 seats for each of the 10 shows and tickets sell out almost immediately. I went to buy mine the morning the tickets were available, arrived 15 minutes after the office opened, and found myself 66th in line. The entire process took hours!