The lost Leonardo: The Battle of Anghiari

One of the great mysteries of the art world involves one of the most important commissions of Leonardo da Vinci’s career: painting one-third of a 174-foot wall of one of most the massive and politically prestigious rooms in Europe, the Council Hall in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. Oh, and to make life interesting and present a bit of a challenge, Michelangelo was commissioned to paint the opposite wall. Michelangelo had just finished the David. Leonardo The Last Supper. They were both hired by a man who understood just a little about competition and manipulation, Machiavelli. It was the only time they would work together on the same project.

Leonardo was 51 and Michelangelo was the hot, up-and-coming young artist at 28. The two men couldn’t have been more different. Leonardo was known for his grace, elegance, sparkling conversation, and mentoring a circle of younger artists. Michelangelo was disheveled, brooding, short-tempered, solitary, often filthy, and the last thing he wanted was any mentoring from Leonardo. Michelangelo was openly disdainful of Leonardo when they encountered each other in public. Both men were gay, but Leonardo seemed to have been more public and comfortable with it. Michelangelo was more tortured about his sexuality and is reported to have decided to be celibate.

The Council Hall was the center of power in Florence when Florence was at its apex. It had just become a republic after the long dominance of the Medici and there was a period of peace. They expanded the hall to seat 500 representatives (it’s now called the Salone dei Cinquecento) and the subjects of the paintings were chosen to convey Florence’s military might and power. Leonardo chose a battle that had happened on June 29, 1440 along the Tiber river in the valley outside the small, fortified hill town of Anghiari (which happens to be our stomping ground.) The battle, which pitted Milan against Florence—one of Florence’s few military victories—involved forty squadrons of mounted soldiers and 2,000 on foot. The battle was a turning point for Florence because Milan gave up trying to conquer the rival city. However, Machiavelli was disdainful of the battle as only one soldier died, and that was from falling off a horse.

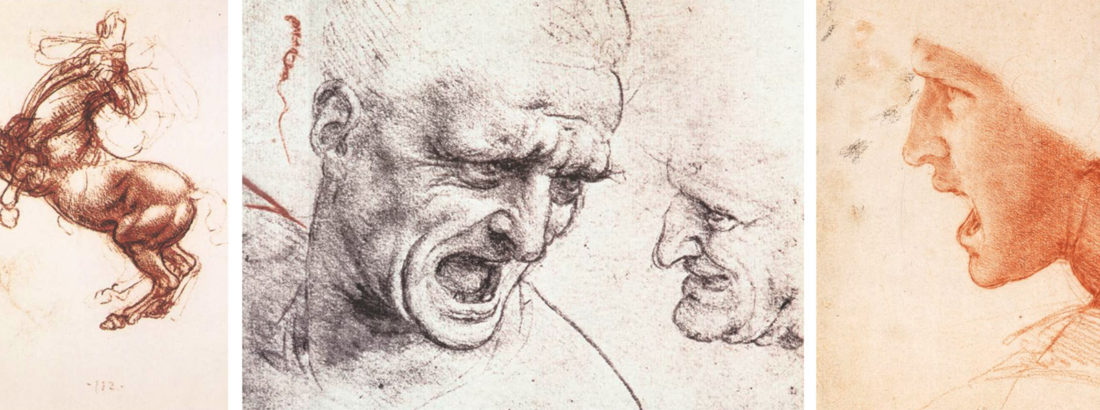

Leonardo decided to make the central scene a small group of soldiers vying for a standard flag rather than to portray the large scale of the battle. He was as fascinated by showing the struggle to the death of the horses as much as the men, and did dissections and studies of the similarity of expression and facial muscles of each species. Leonardo wanted a softer and more luminous look than traditional fresco techniques could give, so he decided to use oil paints. There are many entries in his notebooks about how to convey the reality of battle—how much dust is kicked up and how high in the sky it hangs, how bodies are dragged through bloody mud, the noise—and he felt that this newer technique would let him marry the nuance of oil painting with the grandeur of frescoes.

He completed the cartoons for the painting, mounted them with a flour-based paste, designed an innovative scissor-type moveable scaffolding, and went to work. In addition to experimenting with paint he also experimented with a base layer that was thought to be a mix of resin and wax. In his prototypes it dried well, but on the wall it remained wet, despite the fires he lit in the hall to promote drying. Not only did the preliminary work not dry, it started to melt.

Leonardo attempted to continue work, but was well-known for procrastination and not finishing projects. The City of Florence renegotiated his contract so that he would have to repay all his fees and forfeit his work if it wasn’t completed by 1505. His deadline came and went, and the painting wasn’t finished. Then a huge storm hit. The cartoon was thrown to the floor and deluged by water from the rain and a large overturned bucket. The project was all but dead.

Meanwhile, on the other wall, Michelangelo was not doing a lot better. He started the project and then got called away to do the Pope’s tomb and Sistine Chapel in Rome.

So the two unfinished paintings sat, facing off, adorning one of the most important rooms in Italy. People came from all over to see Leonardo’s unfinished work, which contemporaries described as some of his best, even in its unfinished state.

In 1565, Vasari, who is the first art historian and adored both Leonardo and Michelangelo, was hired to oversee the redecoration of the Palace and creating finished paintings in the Salone dei Cinquecento. So he painted over the work of Michelangelo and Leonardo in his own paint by the acre style, which remain in the room today.

What we know of the painting (the images above) were actually done by Rubens a century later from contemporary studies of The Battle of Anghiari.

But the story may not end there. An air gap was discovered behind the Vasari, and a team led by Mauricio Seracini from University of San Diego, who is one of the leading diagnosticians of Italian art, got permission to drill through previously restored sections of the Vasari to see what might be behind. They found traces of pigment that matches what Leonardo was experimenting with at the time, and many historians doubt that Vasari would have painted directly on top of two of his most revered masters. (There is also a mysterious phrase on one of the flags in Vasari’s work, located where no one who was not on scaffolding could read, that ways “Cerca Trova,” “He who looks will find.”)

So you’ve got some compelling leads that one of the greatest paintings of all time might be behind this wall, but you are in Italy, so what happens? The project to uncover what might be there is shut down by a group of art historians who question whether this experiment, which is harming already damaged sections of the Vasari, goes against the Italian constitution, and call the police saying it might be illegal. Oh, and they hated Renzi, who was Florence’s Mayor at the time and was in favor of the exploration.

And there the story remains since 2012. If the painting is ever uncovered it require massive meddling with the Vasari (like pouring glue all over it, putting another substrate over the front, peeling the painting off, and putting it on another base. What could go wrong?)

And the Leonardo might just be a smudge of running pigment. But, how amazing that this possibility even exists.

If you want to know more about Leonardo I’ve enjoyed Walter Isaacson’s 2017 book, Leonardo Da Vinci.

No Comments